Data Directed Design

#Where does recursion come from?

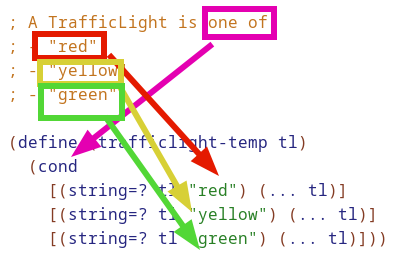

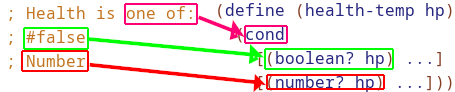

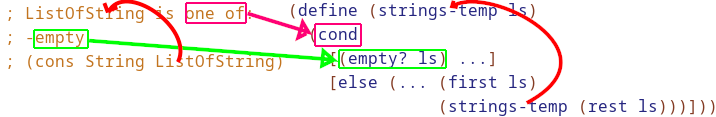

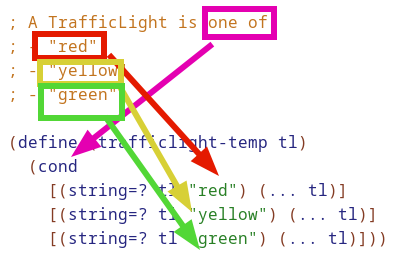

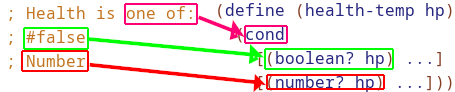

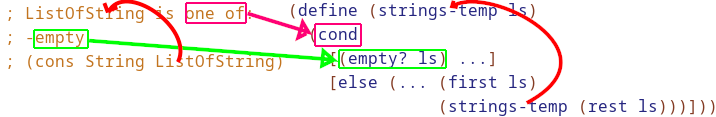

It comes from the idea that the structure of the code should mirror the structure of the data definitions. Here we can see this done in some of the data definitions we’ve done before:

#Enum data

#Union data

#Self Referential Data(Recursion)

Trippy I know.

#The two main things you need to focus on are:

Base case: what we do when the list is empty, aka the termination condition

How to contribute/combine to the base case

Focus on the 1 list long case and how you combine it with the base case to achieve the intended purpose, and trust that it will just work for a list of any length

#Self reference template

; ListOfNumbers is one of:

; - empty

; - (cons Number ListOfNumber)

; interp. a list of numbers

; examples:

(define one-ls (cons 99 empty))

(define two-ls (cons 4 (cons 6 empty)))

(define three-ls (cons 1 (cons 8 (cons 5 empty))))

(define (list-of-nums-temp lst)

(cond [(empty? lst) ...] ; ◄────── (1) ... base case

[else

(... (first lst)

(list-temp (rest lst)))]))

; ▲

; │

; │

; (2) ... contribution to the base

Notice how the Data Definition maps to the code. It’s a one of, so we need a cond with two matching cases. In the 2nd case, we simplify what would be (cons? lst) to else instead for short. Always use the derived template as starter code, as all recursive functions will have this structure.

#Recursion Exercise

Use the design recipe and recursive template to work through the following 3 problems

sum-price , count-items , has-peanuts?

; ListOfNumber is one of:

; - empty

; - (cons Number ListOfNumber)

; interp. a sequence of numbers

; TODO: TEMPLATE

; sum-prices : (ListOfNumber -> Number)

; produces the sum total of the numbers in the given list

; count-items: (ListOfNumber -> Number)

; produces the amount of numbers in the given list

; ListOfString is one of:

; - empty

;- (cons String ListOfString)

; interp. a sequnce of strings

; TODO: TEMPLATE

; has-peanuts? : (ListOfString -> Boolean)

; produces #true if the list contains "peanuts"

answer

; Notice the similarities between 3 recursive functions

; ListOfNumber is one of:

; - empty

; - (cons Number ListOfNumber)

; interp. a sequence of numbers

(define (list-num-temp num-ls)

(cond

[(empty? num-ls) ...]

[else

(... (first num-ls)

(list-num-temp (rest num-ls)))]))

; sum-prices : (ListOfNumber -> Number)

; produces the sum total of the numbers in the given list

(check-expect (sum-prices empty) 0)

(check-expect (sum-prices (cons 0.50 (cons 4 empty))) (+ 4 0.50))

(check-expect (sum-prices (cons 4 (cons 1 (cons 7 empty)))) (+ 4 1 7))

(define (sum-prices num-lst)

(cond

[(empty? num-lst) 0]

[else

(+ (first num-lst)

(sum-prices (rest num-lst)))]))

; count-items: (ListOfNumber -> Number)

; produces the amount of numbers in the given list

(check-expect (count-items empty) 0)

(check-expect (count-items (cons 33 (cons 4 empty))) 2)

(define (count-items num-lst)

(cond

[(empty? num-lst) 0]

[else

(+ 1

(count-items (rest num-lst)))]))

; ListOfString is one of:

; - empty

; - (cons String ListOfString)

; interp. a sequnce of strings

(define (list-string-temp str-ls)

(cond

[(empty? str-ls) ...]

[else

(... (first str-ls)

(list-string-temp (rest str-ls)))]))

; has-peanuts? : (ListOfString -> Boolean)

; produces #true if the list contains "peanuts"

(check-expect (has-peanuts? empty) #false)

(check-expect (has-peanuts? (cons "vanilla" (cons "chocolate" empty))) #true)

(check-expect (has-peanuts? (cons "mint" (cons "peanuts" empty))) #true)

(define (has-peanuts? str-lst)

(cond

[(empty? str-lst) #false]

[else

(if (string=? (first str-lst) "peanuts")

#true

(has-peanuts? (rest str-lst)))]))

#Similarities

Here’s a table in the main ways they are similar but differ:

| Function |

Base |

Contribution of first |

Combination |

has-peanuts? |

false |

(string=? (first str-lst) "peanuts") |

(if <condition> #true <recurse>) |

sum-prices |

0 |

(first nums) the price itself |

+ |

count-items |

0 |

1 |

+ |

Look in the BSL documentation for the combinator. If it doesn’t exist, wishlist it!

I’m sure you’re feeling:

Wait a minute, when I write the recrusive call, I’m assuming this functions fullfills its purpose statement and just works? But I haven’t even finished writing the function yet, in fact I’m still in the middle of writing it! It’s weird... It feels like magic, like cheating! Not to mention purpose statements are just comments!

#How does it work?

The individual/micro/mechanical operations of recursive functions expliots the rule that we’ve learned all the way in the start of the course, and that is that function operands(aka parameters, inputs, arguments) need to be values before the operator can do its job. Let’s explore this in a bit more detail!

Use the stepper and step through this expression:

(+ (* 2 6 (/ 4 4)) (- 1 1))

This is the order of calls:

Calling:

+ is called 1st

* is called 2nd

/ is called 3rd

- is called last

Even though + is called first, it has to wait until all of its operands resolve into values, so it is executed last. The order of the operations that executes is different:

Executing:

/ is executed 1st

* is executed 2nd

- is executed 3rd

+ is executed last

Note that calling and executing are two different things.

Calling a function is like putting it on a todolist.

Executing a function is doing the operation.

As a function calls itself, it will build a sort of “chain” of calls until it hits and stops at the base case. Let’s see this in action using the stepper to step through the call to:

(sum-prices (cons 4 (cons 1 (cons 7 empty))))

(+

444

(+

1

(+

7

(cond

[(empty? '()) 0] ; <- the base case

[else

(+ (first '()) (sum-prices (rest '())))]))))

; hitting the base case:

(+

4

(+

1

(+

7

(cond

[#true 0] ; <- the base case

[else

(+ (first '()) (sum-prices (rest '())))]))))

; the "final" expression, a chain of calls:

(+

4

(+

1

(+

7

0))) ; <- the base case

; ^ re-written more neatly without the spacing:

(+ 4 (+ 1 (+ 7 0)))

#Table method

It is often better to write out the execution in a table format for more of a birds eye view. Here is the execution of sum-prices when it is given the list (cons 4 (cons 1 (cons 7 empty))):

| step# |

lst |

(empty? lst) |

(first lst) |

(rest lst) |

| 0 |

(cons 4 (cons 1 (cons 7 empty))) |

false |

4 |

(cons 1 (cons 7 empty)) |

| 1 |

(cons 1 (cons 7 empty)) |

false |

1 |

(cons 7 empty) |

| 2 |

(cons 7 empty) |

false |

7 |

empty |

| 3 |

empty base case: 0 |

true |

ERROR |

ERROR |

(+ 4 (+ 1 (+ 7 0)))

Note that the base case produces: 0

Notice that the list gets smaller on each iteration step

#Top mistakes students make when doing recursion

- Being hung up on the individual mechanical operations of each recursive call

- Not writing or using a template as a starter

- Not using the stepper/writing things down in a table

- Not having a clear purpose statement and trusting it, and focusing too much on the code. Purpose statements should focus on what the function computes not how it goes about it

- Forgetting to make sure the a recursive function calls itself

- Not having a good base case

- Not having the functions follow the signature

#Debugging recursive functions

- Comment out all tests except the failing one, and use the stepper

- Write out in a table the first and rest of every call to get a birds eyeview: beginning student tables

#Why is recursion hard?

1. Default mindset: Humans think sequentially (“do A, then B, then C”).

Recursion demands: “Solve a smaller version of the problem first, then combine results”—a backwards or self-referential logic.

Example:

Iterative: “To climb 10 stairs, step 1, then 2, then 3...”

Recursive: “To climb 10 stairs, first know how to climb 9 stairs, then add one more step.”

Why it feels unnatural: Recursion asks us to delegate the work before seeing the result, which feels like “cheating”, compared to the iteration where we can see all the previous steps before us more easily.

2. The Fear of the Unknown

Desire for control: People want to trace every call to feel “sure” it works.

Recursion’s opacity: Each recursive call hides complexity, creating unease.

3. Infinite Loop Anxiety

Base-case paranoia: Missing or incorrect base cases lead to infinite recursion (and stack overflows). In contrast to iteration, we have a more intuitive grasp at when we end up front with very little chances of infinite looping.

The idea of why recursion works is similar to proofs by mathematical induction.